Having worked with companies to implement tax governance frameworks for over 15 years, I’m seeing the first signs that tax governance is truly going mainstream.

For a number of years, the ATO has been driving a greater focus on governance by large companies and demanding that tax is aired in the boardroom. In recent times, the ATO has been seeking to broaden this to a much greater proportion of corporate taxpayers. Starting with the release of the Tax Risk Management and Governance Guide in 2017, followed by recent moves to extend their Streamline Assurance Reviews (SARs) program to the top 1,000 corporate taxpayers, the ATO is driving a keen interest in tax governance to a much wider group of companies. Ultimately, the objective is for this idea to find its way into private groups and family businesses.

This has left many now asking “what is expected of us now?” and importantly, “what do we do about it?”.

The ATO’s program targeting top 1,000 taxpayers

The ATO ‘s ‘top 1,000 program’ aims to achieve greater assurance that the largest public and multinational companies are paying the ‘right amount’ of income tax. The program covers large public and multinational companies, generally focusing on taxpayers with turnover above $250m.

The ATO is intending to obtain that assurance by engaging with taxpayers through the SARs process under the ‘justified trust’ concept, which is based on an OECD idea that the confidence of revenue outcomes is better served by  obtaining evidence of effective controls and compliance by ensuring control frameworks are in place and are tested, as opposed to more traditional compliance methods such as random audit selection and targeted “risk reviews”.

obtaining evidence of effective controls and compliance by ensuring control frameworks are in place and are tested, as opposed to more traditional compliance methods such as random audit selection and targeted “risk reviews”.

SARs, originally targeted at the top 100 companies, has a key focus on the adequacy of taxpayers’ tax governance, rather than focusing on identifying specific transactions and tax risks.

To achieve justified trust, the ATO is seeking objective evidence to conclude that a particular taxpayer did, in fact, pay the right amount of tax. This is a higher level of assurance than confirming certain risks do not exist. Consequently, the ATO is shifting their focus on how risks are identified and managed, and away from the specific transactions that might carry heightened tax risk.

What does the ATO expect now?

The ATO’s guide sets out its expectations for taxpayers in this new world of justified trust and tax assurance.

Fundamentally, the ATO expects all corporate taxpayers to have a tax governance framework in place, with policies and procedures which demonstrate how risk is managed. Ultimately, such policies and procedures, and the controls embodied in the procedures, will need to be tested.

Clients that have been selected recently for a SAR are facing questions like:

- Describe your approach to the ATO’s guide including whether you have undertaken a gap analysis of current policies and procedures against the ATO’s guide. Have you identified compensating controls where applicable?

- Have you applied the self-assessment procedures to test that controls are operating effectively?

- If the self-assessment procedures have been applied, provide details of any control deficiencies and how those deficiencies have been remediated.

The information requested in the SAR questionnaire is extensive and demands real evidence of the operation of the tax governance framework, including all relevant policies, procedures, tax manuals and the like.

Measuring the governance gap

Possibly the most frequent question I’ve had from clients this year is “how do we meet the ATO’s expectations in practice?”.

For almost all companies, this means that having a documented tax risk policy alone is no longer sufficient, and for many corporates, even at the big end of town, the governance gap will be substantial.

In addition to the guide, the ATO has also attempted to provide further help to taxpayers to classify the extent of their governance gap. In June this year, the ATO released some additional commentary on how they will assess a company’s tax governance enabling taxpayers to determine the size of their “governance gap”. The guidance stratifies taxpayers into three distinct stages:

STAGE 1 | A TAX CONTROL FRAMEWORK EXISTS |

STAGE 2 | THE TAX CONTROL FRAMEWORK IS DESIGNED EFFECTIVELY |

STAGE 3 | THE TAX CONTROL FRAMEWORK IS WORKING IN PRACTICE |

While in practice many companies have a board-endorsed tax risk policy document, the lack of documented evidence of the tax governance framework, with documented procedures and testing plan, quickly becomes apparent.

Stage 2 is difficult to satisfy for most companies, due to a lack of objective evidence of the effective design of a tax control framework. A documented gap analysis to the ATO’s guide will go a long way to providing evidence of the design of the framework.

That gap analysis will also provide the basis for determining where the effort needs to focus in future.

Stage 3, which requires taxpayers to demonstrate that the tax control framework is working, will take companies on a journey to more sophisticated tax governance procedures. Think fully documented policies and procedures and an  ongoing assurance program with independent testing of controls. For many companies, this will be an aspiration, even for the largest corporates with substantial in-house tax functions.

ongoing assurance program with independent testing of controls. For many companies, this will be an aspiration, even for the largest corporates with substantial in-house tax functions.

How do you bridge the governance gap?

Bridging the governance gap will require a level of maturity and sophistication that will go well beyond the board-endorsed tax risk policy that was the first rung on the ladder. The new world will require more structure, documentation of policies and procedures and an independent controls testing program, much like any other area of the financial reporting processes.

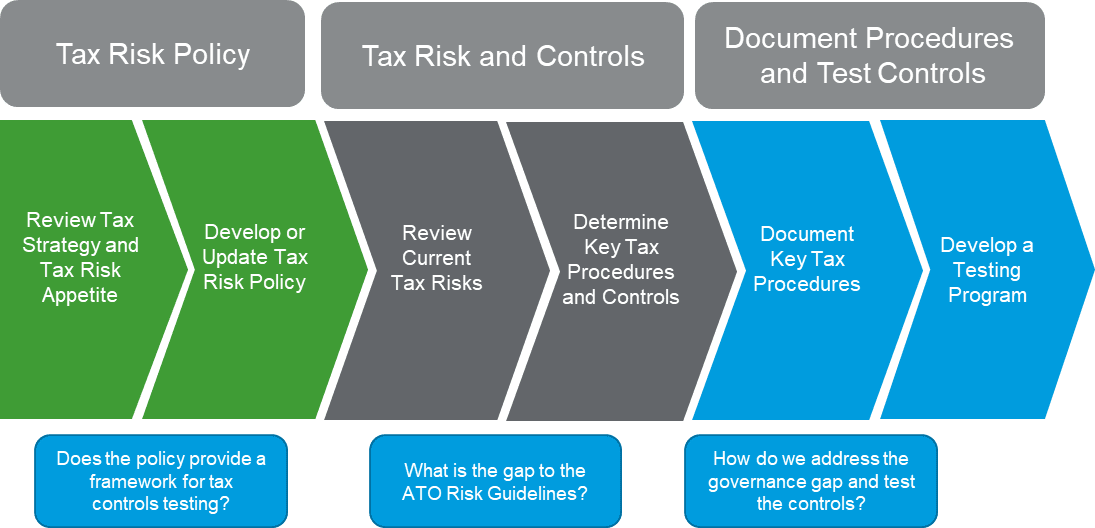

An approach to implementing tax governance procedures and bridging the governance gap is described in the following process.

It starts with documenting or updating the tax risk policy (if one already exists) and moves through the documentation and testing of key controls, as set out below:

A key message for finance and tax teams embarking on this process is, one size doesn’t fit all and beware of ‘off the shelf’ solutions that end up being just words. To be effective, a governance framework should provide a real, practical tool for managing risk.

FOR MORE INFORMATION ON BRIDGING THE GOVERNANCE GAP

For more information on bridging the governance gap and tax governance frameworks, please contact your local RSM office or speak to your local RSM tax adviser.