We have owned the Internet. Our companies have created it, expanded it, perfected it in ways that… [European firms] can't compete. And oftentimes what is portrayed as high-minded positions on issues sometimes is just designed to carve out some of their commercial interests.

Barack Obama

The internet is the defining meme of globalisation. It is impossible for us to conceive of a world without the internet. The World Wide Web, as the acronym in every web address repeatedly reminds us, rises above the physical limitations of geography effortlessly. There are no boundaries in the digital sphere and audiences – whether for business or an individual – are global. The largest companies globally are increasingly associated with technology, and big data is the mountain they all mine today for their global profits. The future – whether blockchain, artificial intelligence, the gig economy, augmented reality or the Internet of Things – is unfailingly digital and intrinsic to the future of global growth.

But this posterchild and its borderless model are under threat. Deglobalisation – the emerging paradigm in an economically frustrated world – is also going digital.

Today, the internet is fast becoming another battleground of protectionism and populism, while cash-strapped governments look to tap into the digital gold rush. The result is the emergence of boundaries and the erosion of global business models, with stark implications going forward.

"The internet is the defining meme of globalisation, and without action, a new meme – the splinternet – may emerge to define the poorer deglobalised future we all fear."

Much of this has crept up unawares. The internet is typically viewed through an American prism, not surprising given its history and the predominance of US firms.

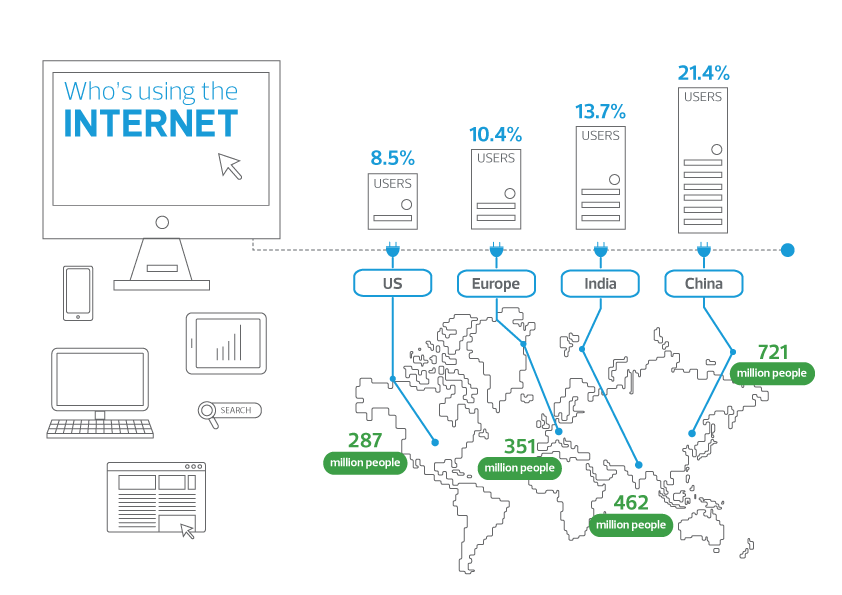

But today, only a mere 8.5% of internet users – some 287 million people – are in the US, compared to 21.4% (721 million) in China and 13.7% (462 million) in India. Europe – even without the UK – has 64 million users more than the US today. That differential will accentuate further in coming years as penetration levels in emerging markets catch up with the developed world.

The growth and rising clout of these nations as internet hubs reflects a huge geographic shift. It also changes the nature of the debate over the governance and culture of the internet, given the differing economic priorities, commercial interests, cultural sensitivities and socio-political landscapes.

In this environment, the unwritten organic constitution of the internet cannot survive. The question of who actually owns it and who controls it is increasingly coming to the fore, especially as it intrudes onto economic development, societal norms and security concerns.

China has already set up the ‘Great Firewall’ of China, which limits access to politically unpalatable websites, screens search results and the like. In the developed world, the US and UK have clashed with tech firms, as they seek access to private information, backdoors into popular platforms and a weakening of encryption standards in the name of combating terrorist threats. On September 20, for example, the British Prime Minister Theresa May called on internet platforms to remove extremist content within two hours of it being shared.

"These efforts to control the flow of data threaten to raise the cost of doing business, leech protectionist sentiment and economic nationalism into the digital sphere, and in extremis, limit digital trade."

Deeper societal clashes are also emerging. In October 2015, the European Court of Justice struck down the 15-year-old Safe Harbor data transfer agreement that allowed US firms to transfer EU personal data to the US for processing. In September 2015, Russia passed a data localisation law requiring companies to store data on Russian citizens on Russian soil, and further strengthened enforcement powers in January 2017.

These efforts to control the flow of data may have been born amidst the Edward Snowden revelations of widespread tapping by US intelligence agencies, which accentuated tensions and bled trust. But they also reflect the fundamental tensions of nations in a globalised world, as countries worry about political stability, the boundaries of their rule of law and unknown threats to the status quo.

Beyond geopolitics, however, these efforts to impose the constraints of nationhood also have a chilling effect on commercial enterprise. They threaten to raise the cost of doing business, leech protectionist sentiment and economic nationalism into the digital sphere, and in extremis, limit digital trade as local legislation – consciously or not – favours local industries.

In 2015, Canada banned foreign providers from bidding on its new email platform for federal organisations, and introduced a requirement for support personnel to be Canadian citizens, citing a national security exception. In 2013, the US banned the Departments of Justice and Commerce from buying IT systems “produced, manufactured, or assembled” by entities “owned, directed, or subsidized by PRC”. Europe more recently has outlined plans to create a new "digital single market" simplifying rules for operating across EU borders, though also including new regulations for online “platforms”.

There are commercial imperatives hidden within, alongside purer security and privacy concerns. In a world looking to technology for future economic growth, nurturing local industry is now key to economic development. China’s Great Firewall, for example, successfully sheltered local titans like Sina Weibo and Baidu from foreign competition.

The collective impact is a wave of emerging digital protectionism. There is now a growing cost of localisation and storage – regardless of location – coupled with growing policy, political and litigation risks. Added to this mix are the ramifications of incipient populism in the real world. As technology reshapes the global economy, governments are struggling with the socioeconomic fallout of disappearing jobs amidst lacklustre economic growth. There is a dawning realisation that much of this digital economy sits beyond their fiscal grasp, resulting in growing clashes globally over the taxation of tech firms like Google and Apple.

Over time, these diverse fractious fights will eventually reduce flows of data and in turn, digital trade. This would severely impair today’s business models that increasingly look to global audiences for growth; rely on mining and selling data in some form to generate revenues; and minimise costs by picking the lowest cost and most tax efficient digital supply chain globally.

Though technical and cloaked in code, there is a digital tragedy of the commons unfolding today. As different nations grapple for their share of the digital pie, companies are being forced to localise, individuals are losing faith and the global nature of the internet – not to mention its potential – is fast disintegrating in the absence of any overarching care.

This digital clash between global and local mirrors, threatens and accentuates the same risks as blind populism and protectionism in the wider global economy today.

Left unchecked, the digital economy will fracture and shrink further.

And without action, a new meme – the splinternet – may emerge to define the poorer deglobalized future we all fear.