Protectionism and populism are on the rise in the global economy. Businesses are starting to ask: has globalisation, which has helped to expand the world economy and raise millions out of poverty, had its day? For company leaders, this is one of the biggest challenges of our times – with serious implications for how they lead their businesses.

It affects planning, strategy and hiring. They need to ensure they have access to the right expertise and insight to enable their organisations to adapt. In a fast-changing environment, leaders must be able to plan for scenarios over one, three and five years or even more. Even if they end up having to update their strategy due to unforeseen circumstances, it is better to have a plan than be without one.

In recent decades, an increasing number of small and middle-market businesses have aspired to become multinationals, aiming to benefit their staff, shareholders and customers by joining the global economy. It is becoming a bumpier ride, however, one for which they will need to be smart, agile and well prepared. Yet many leaders have barely begun to think through what the impact might be.

We should not write off the global political economy just yet. While things are certainly in flux, there are reasons to hope that a damaging bout of “deglobalisation”, such as that which happened in the early 20th century, can be avoided.

The global economy is recovering: the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development forecasts growth of 3.7% in 2018, close to the 1990-2007 average. These days it is not only manufactured goods that cross borders, but also knowledge, data and skills, which are harder to obstruct.

Business leaders need to ensure they have access to the right expertise and insight to enable their organisations to adapt.

Middle-market businesses are not about to give up and retreat behind national boundaries. Leaders are kidding themselves, though, if they think these geopolitical forces will not affect them. The populist surge is affecting trade, taxes and policies – all items covered by any global economy definition. Companies around the world are faced with diverging regulations and protectionist measures. It is something they simply will have to deal with.

In Australia, removal of the 457 visa, the main route for employers to sponsor skilled overseas workers to work temporarily, makes it harder for expanding companies to find international talent. Brexit in the UK, if not handled carefully, threatens to introduce new barriers to trade and recruitment. The US has withdrawn from the Trans-Pacific Partnership and is renegotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

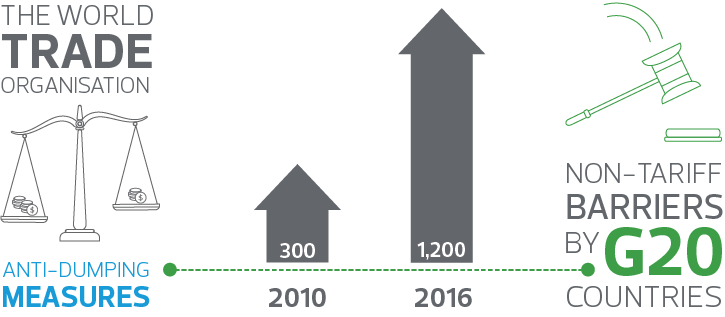

Although there has so far been no general 1930s-style increase in import tariffs, there is a rise in other forms of protectionism. The World Trade Organisation calculates that non-tariff barriers operated by G20 countries, such as anti-dumping measures, grew from about 300 in 2010 to more than 1,200 by 2016.

The ground is constantly shifting. Multinationals of all sizes must cope with changes to tax rules on issues such as transfer pricing. The European Commission’s probe into the Ikea brand’s tax arrangements, for example, are part of a four-year crackdown on what it sees as aggressive corporate tax avoidance. US President Donald Trump’s reforms aim, among other things, to encourage companies to repatriate almost $3tn of earnings, an amount which is, of course, a landmark in the global world economy.

Faced with this complex environment, what can those who run middle-market companies do? Good scenario planning becomes vital. They will find, though, that the skillsets needed are very different to ones that companies are familiar with: they may have to hire or buy in analytical expertise that they do not currently possess. Most managers are focused on their day-to-day business. They will need help to guide them through the quicksand of geopolitics, economics, trade policy and demographic change.

The need for skilled workforces becomes more vital than ever: leaders must ensure that their human resource policies are calibrated to attract and retain the best people. Pressure for tighter immigration controls is growing in several countries, so only the best employers will be able to attract scarce talent if the supply is restricted. The ‘war for talent’ will become more intense.

The middle market could benefit from the renegotiation of trade deals, as they provide an opportunity for adjustments to take new business areas into account, such as digital services.

It is hard to imagine that borders could close entirely or for long: international migrants are vital to the global economy in an interconnected world where transport, the internet and mobile communications make it easier to move. But new controls could get in the way of doing business. Companies must be prepared.

In the UK, for example, net immigration from the EU has already dropped to its lowest level since records began, because of the weaker pound and the anticipation of Brexit. Heads of businesses across the world need to make sure they are equipped to compete for and develop whatever talent is available.

These shifts in the global economy may, of course, bring opportunities as well as threats. Renegotiation of trade deals provides an opportunity to adjust them to take account of new areas such as digital services, which did not exist when agreements such as NAFTA were drawn up. The middle market, which has strengths in the digital world, could benefit.

China’s desire for a bigger role in the global economy, through projects such as its $900bn ‘new silk road’ initiative to facilitate trade between Europe and Asia, may create new opportunities for companies to get involved in the Chinese supply chain. There are practical and political obstacles, however, and many fear a US-China trade war over the coming months.

International business brings many benefits: according to research by think-tank, the US Middle Market Center, the most internationally focused middle-market exporters and importers tend to be the fastest-growing companies.

However, leaders need to carry out careful, strategic planning to meet the many challenges they face, asking themselves at every turn: what is the state of the global economy and how is it affecting business? Cautious engagement seems the wisest path. They must partner with the right advisors, research individual markets carefully, anticipate policy shifts and adapt to them more swiftly and effectively than their competitors.

If they do this well, small and middle-market companies can continue to thrive in the global economy. It is time for company leaders to step up to the plate. Their business’s future success, and even survival, depends on it.

Jean Stephens

CEO, RSM International

Related Insight

re-emerging markets and the road to reglobalisation