Prospects for manufacturing growth in South Africa

There’s no doubt that the new government of national unity (GNU) in South Africa has sparked a modest resurgence in business confidence, as shown by the South African Chamber of Commerce and Industry (SACCI) business confidence index.

This is confirmed by positive data from the Bureau of Economic Research at Stellenbosch University. We’re a long way from where we need to be as a country, but we’ll happily take what good news we can get. Manufacturing output was up 1.7% in July 2024 over the previous year which is better than the 0.4% GDP growth achieved in the second quarter of this year. Manufacturing has the potential to pull the economy out of its multi-year funk.

This article focuses on the prospects for manufacturing growth in SA, and we have identified five broad thrusts that will impact this sector.

The food and beverages sector

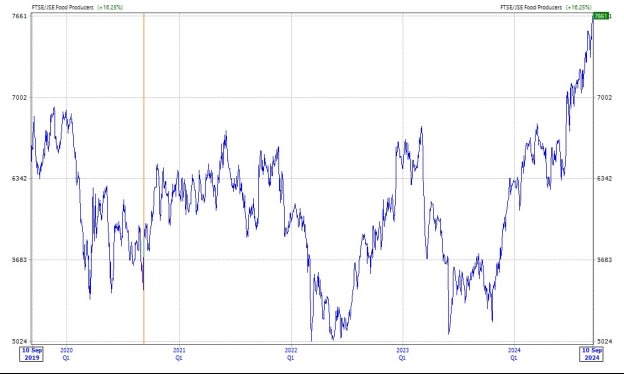

This sector has demonstrated its resilience to the knocks and bruises of SA’s recent economic turmoil. The graph below tell the story of what investors think of the food sector on the JSE. It’s interesting to note that the Food index is the highest it’s been in five years. Research by consultancy group Niras expects the SA beverage market to grow at 5.2% a year to 2028, with new themes helping determine the pace of this growth, such as a growing preference for healthier and more natural beverages, as well as craft beers and premium alcoholic drinks.

The earnings for food companies listed on the JSE have grown 7.3% a year over the last three years, and revenue by 11% a year. Areas that are likely to experience growth are breads and cereals, confectionary, meat, fruits and nuts, and – a big one – pet food. The trends reflect expected demographic patterns, with a growing middle class (and hence pets) and specialty foods.

JSE Food Index

Source: Share Magic

A key focus for food and beverage producers will be waste reduction, energy efficiency, reduced water consumption and streamlined production – all aligning with ESG (environment, social and governance) goals that are being demanded by legislators and customers.

Combined, this suggests food and beverages will outpace growth in other sectors of the economy for the foreseeable future.

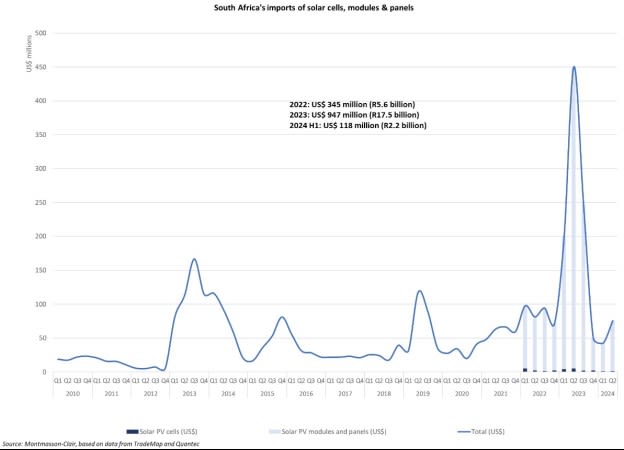

Renewable energy

With loadshedding now largely behind us, demand for solar panels has plunged. The graph below from Trade and Industrial Policy Strategies (TIPS) senior economist Gaylor Montmasson-Clair tells the story. However, it would be wrong to think the electricity crisis is behind us, bearing in mind that Eskom has requested the National Energy Regulator of SA (Nersa) to approve a 44% tariff hike for the coming year. It seems unlikely they will receive anything like this, but consumers can certainly expect electricity tariff hikes of 2-3 times consumer inflation in the coming years. The debt problems at Eskom, and the escalating cost of producing energy, remains an albatross around the neck of Eskom, government and taxpayers.

Consumers can inoculate themselves against these tariff hikes to a large extent by installing solar power systems and by removing themselves as much as possible from the grid. Once the impact of these looming tariff hikes becomes apparent, consumers will discover a new use case, aside from loadshedding, for installing rooftop solar systems. We can therefore expect steady and sustained demand for these systems going forward, impelled by the kind of programmes launched by the City of Cape Town and Midvaal, south of Johannesburg, to reduce dependence on the Eskom grid. We expect to see continued growth in the entire eco-system dedicated to energy efficiency, alternative power production, including nuclear. ESG will remain a powerful propellent of this dynamic. It’s also clear that the costs of renewable energy systems have reduced sharply due to the increased volumes flowing into the country, making these accessible to a far larger market.

Source: Montmasson-Clair, based on data from TradeMap and Quantec.

Personal care and health

The personal care market is expected to grow from $3.35 billion in 2023 to $4.2 billion in 2028, a compound annual growth rate of 4.6%. According to Mordor Intelligence, this growth will be driven by population growth, urbanisation and the increasing affordability of products available to the roughly 20 million women of working age in SA. There’s also growing demand for men’s personal care products, with a trend towards more natural and organic ingredients. Another trend is the number of people starting online businesses offering products for health, such as supplements, vitamins and energy boosters (as well as for weight loss). An area of growth to watch is for anti-aging cosmetics and supplements, particularly for the 5.6 million South Africans above the age of 65. The market is dominated by companies such as Unilever, Estée Lauder, L’Oreal and Natura, but many smaller companies are starting to muscle into this space, and we see this as an area of future disruption, particularly if smaller entrepreneurs are able to access financing and business start-up assistance from both private and public sector sources.

Innovation as a driver of economic growth

Virtually every major company in the world is considering or actually investing in AI. Research by McKinsey outlines a future where massively enhanced computational power, with connectivity between the various parts of a production chain, processed through AI and work automation systems can reduce machine downtime by 30-50%, increase labour productivity by 15-30% and improve product throughput by 10-30%. In a world of tightening margins, these are massive numbers. There are numerous fascinating developments in industrial automation and AI that provide a glimpse into the near future. For example, generative design – instead of telling ChatGPT to generate text or images, you instruct it to design products, detailing what materials should be used, the manufacturing methods, the costs, the size and weight of the product – and out comes a design blueprint.

Then there’s predictive maintenance, where an array of sensors and instruments are calibrated to detect faults before they occur. These predictive maintenance systems are already widely in use in mining processing units, but they are becoming increasingly sophisticated. They can alert maintenance managers when the brakes on heavy duty trucks are about to fail, or when underground cooling systems need servicing. We are also entering the era of fully automated mining, and human-less factories that can operate 24/7. Vehicle manufacturer Ford is already using ‘cobots’ – a robot that works alongside a human for tasks such as sanding and polishing, assembly, as well as quality control. The net impact of this will be to drive down the costs of production, improve quality and drive consumer spending. South Africa is some way behind the curve on this, but the technology lag will likely get shorter and shorter.

How can SA’s manufacturing sector leverage these technological shifts?

For the government’s part, by lowering tariffs in industries that can create jobs and wealth locally. The days of labour cost arbitrage are coming to an end. We should, in theory, be able to manufacture as cheaply in SA as in China, provided we can scale accordingly. That will require a far more congenial regulatory environment for business, and we’re a long way from that.

It’s clear from some of the trends discussed above that technology has a deflationary effect – we’ve seen the costs of solar panels drop, while automation and AI in other fields will have a similar impact. The need for unskilled general workers will diminish, and that will force people in fields such as computer programming, maintenance, quality control, design and even law to reskill in ways that embrace this technological shift. We are still a long way from replacing lawyers, factory workers or programmers, but those employed in these fields will have to become AI and automation specialists. Programmers will be far more efficient in their use of time, thanks to AI. Governments are beginning to understand these impacts and identify niches that can unleash greater manufacturing capacity. In SA’s case, the long-awaited case for minerals beneficiation is now tantalisingly close.

These technological shifts can – and should – act as catalysts for change. There is no question that SA has undergone a process of de-industrialisation that commenced with our accession to the World Trade Organisation in the 1990s. Our clothing, TV and radio manufacturing industries virtually disappeared because they could not compete with the likes of China on costs. Lower tariffs swamped the local market with cheaper goods. That benefited the consumer in the form of cheaper goods, but in a world where labour arbitrage is diminished, SA could again experience a resurgence in manufacturing capacity to feed both the domestic market and the wider region.